- notyrgirls

- Posts

- Ding, dong, the witch is dead

Ding, dong, the witch is dead

Body image and the beautiful teen witches of the 90s

Light as a feather, stiff as a board. Light as a feather, stiff as a board. Light as a feather, stiff as a board. I’ve buried the feelings that this chant summons within me in the darkest corners of my mind, where the old wounds have gone to coagulate. Out of sight, out of mind. Another chant, a mantra, convincing me that these old wounds will stop reemerging from their depths. They don’t.

If you grew up in the nineties and noughties, chances are you played “light as a feather, stiff as a board” in a friend’s room late one night or at a basement slumber party. You would lie on your back as the others formed a circle around you. Each person would place two fingers under your body; usually, one person was at your head and the rest divided equally on either side of you. The seance would begin:

She’s looking pale. She’s looking pale. She’s looking pale.

She’s looking worse.

She’s dying.

She’s dead. She’s dead. She’s dead.

Surrounded by your friends, chanting in unison into the dark, it really did feel like you had separated from your physical body. Together, they would finish the spell and lift you off the ground with ease. Light as a feather, stiff as a board. Levitating just for a moment; snapping out of your death trance almost immediately as the others screamed, spooked by what they had just accomplished.

I loved being a lifter because you got to participate in making the magic. It made you feel powerful and united. I hated being the dead girl because I hated my body. I was convinced, deep down, that it would not work on me. That the weight of my physical self could never be conquered by my best friends’ six fingers. No spell could take on my thighs.

“What are you?”

Libby (to Sabrina): Don’t come in here again. From now on you use the freaks’ bathroom. (Sabrina the Teenage Witch, season 1, episode 1)

In elementary school, after-school daycare was peak play-pretend time, even in my pre-teen years. Maybe because there were fewer kids around after school, when my friends and I would really let loose. One of our favourite games was acting out scenes as the Halliwell sister witches from Charmed. Though I never saw more than a handful of episodes as a kid, I followed my friends’ cues. I also based my portrayal of these witches on the other powerful fictional characters I was more familiar with, whose stories I had been reenacting throughout my childhood.

Super-powerful girls were super-present on screen in the 1990s. The girl-power pop feminism of the era informed fictional portrayals of strong-yet-sensitive types like Serena/Usagi (Sailor Moon), Sabrina Spellman (Sabrina the Teenage Witch), and Buffy Summers (Buffy the Vampire Slayer). These shows are characterized by a constant push and pull between exploring and expanding on the lore of their protagonists’ supernatural abilities, while also centering plots on mundane everyday realities or the growing pains of teenage girldom. Mishaps, miscommunications, forbidden love, drama between friends, rule-breaking, and mischief were as much a part of their worlds as the powers of the moon, talking cats, and vampires. The juxtaposition between natural and supernatural worlds and issues mirrored the main characters’ struggle between their “normal” vs. “abnormal” selves.

Upholding some kind of “normal” facade was always a major part of these storylines. According to media and gender scholar Julie O’Reilly, in order to protect herself and her community, the super-powerful girl at the heart of these shows has to conceal her abilities (52). Often, if discovered, she is labelled a freak. She is asked to explain what she is, othering her as a thing rather than a person. As O’Reilly writes in Bewitched Again: Supernaturally Powerful Women on Television 1996-2011: “The appellation ‘freak,’ even when applied to a beautiful–and superpowered–woman, recalls the tradition of displaying allegedly abnormal individuals for consumption by a voyeuristic public that was popular in the United States in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries” (46). The “freak” fascinates and repulses (56); frightens, confuses, and captivates. But while these teenage girls with supernatural powers exist in the world of monsters, they are anything but monstrous.

Beauty…

In Teen Witches: Witchcraft and Adolescence in American Popular Culture, Miranda Corcoran argues for a teratology (science of monsters) of the teen witch that “pivots on the materiality of the body” (22). Both as an individual and social body, the adolescent girl is “always caught in the process of becoming,” she defies categorization (53). Corcoran describes this as a “leaky” state (53). This leakiness goes back to antiquity, to the humoral theory of the wet and humid (weak) woman, in opposition to the hot, dry, strong man. Menstrual blood, historically associated in western culture to impurity and excess, also marked women as lesser, toxic beings. According to these interpretations, then, the monster was always within, waiting to burst forth through puberty and in adolescence.

But Buffy, Sabrina, and the Halliwell sisters are not warty, ugly crones. They represent a particular feminine construct of witchiness. As a teen, I dreamed of having their magic powers and I pined for their looks. This was a package deal. In “Girl, Unreconstructed”, Rachel Fudge argues: “[G]irl power tricks us into believing that girls are naturally powerful and therefore ignores the many ways their power is contingent on adhering to cultural expectations of female behaviour” (160). Beyond beauty, these expectations also manifested in the characters’ crafted personalities. Sabrina, for example:

These qualities softened her powers. While teenage witches could be vengeful and power-hungry (see: The Craft), the version that was packaged up for younger girls, such as myself, dealt with these themes in more lighthearted ways. If these super powerful girls exist, but they remain “young, white, ‘beautiful’, heterosexual, and economically comfortable,” then what can they truly offer us?

…and the beast

When I hit puberty in elementary school, it felt like my body changed overnight. So did my conversations with friends. In the locker room before gym class, I tried to invent “reasonable” numbers when we started to compare how much we weighed. I didn’t know what the ideal was, but I knew what I looked like in contrast to others. Between 9 and 10 years old, my visibly bony childhood figure ceded to a round pudginess, so much so that a classmate told me I had better start working out to deal with my thighs. “Or they’ll just keep getting bigger,” she said, feigning concern. Those were the first words of a spell that has continued to build for decades, feeding off of comments from others, images across media, and what I saw in reflective surfaces.

When I played pretend, not only did I have supernatural powers–I was also beautiful. I thought the sheer force of my imagination could craft me in their likeness as I aged. The obsession with a particular kind of beauty, the kind that comes from being petite and delicate, became part of every aspect of play. Which of my t-shirts was long and baggy enough to cover my thighs when I wore a bathing suit in my friend’s backyard? How could I avoid wearing shorts in gym class when my legs started sprouting dark hairs? I came up with a hilarious solution to this, reminiscent of the classic portrayal of witch’s socks: I would wear colourful patterned knee-highs, as they covered the hairiest part of my legs.

I even had a pair that were purple and black striped. They also had cherries on them. And were toe socks.

I was loved and privileged; I had (and still have) a family who cared deeply about each others’ happiness and fulfillment. I have many positive memories associated with my childhood. But there was also a deep insecurity brewing, one that I would continue to battle for many years to come: The unshakeable impression that I was fundamentally, immutably ugly. I kept this thought a secret, like when I started menstruating and didn’t want my friends to know. It felt shameful, and embarrassing, and dirty, even in the late twentieth century, when the “moist humoral” bullshit had long been debunked. And no amount of girl-power-teen-witch-bombshell capitalism could change that because I could never actually be those girls. I could only pretend.

Can the crone liberate us?

As I was drafting this newsletter, Jac asked me: “How do you think older crone characters figure in the culture then/today? Are la Befana, Strega Nona, the hag in the forest semi-venerated as a possible antidote to these representations?” I think, in short, yes. But also, it depends. Like with the beautiful witches and super-powered women of the 90s, we have to identify the goal of these representations and who is creating them.

The figure of the witch has not always been gendered. In early modern Europe, men and women were accused of witchcraft. In England, through the transition from agrarian feudalism to industrial capitalism, it became a targeted “campaign of terror against women” for ulterior motives. Poor/lower class and elderly women were overwhelmingly the targets of this campaign. The word “witch”, as Rachel Christ-Doane, education director at the Salem Witch Museum, states in an interview, described a criminal offence. In Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, Silvia Federici argues that those early modern witch hunts were necessary for capitalism to flourish as they created division, sowed fear, and established limitations on the way women could move in the world:

The enclosure of the body thus reflected the enclosure of common lands into private property.

By the late nineteenth century, Christ-Doane explains, “pop culture portrayals like Halloween postcards and advertisements [depicted] witches [as] beautiful, sexy women. Over time, the definition of a witch becomes just a woman with magical powers.” Perhaps in the shadow of capitalism’s success, associating magic power with female ‘goodness’ and beauty was a kind of continued enclosure. It’s in this period that we get L. Frank Baum’s Glinda and the Good Witch of the North and the Wicked Witches of the East and West. The 1939 The Wizard of Oz film adaptation of his book is often credited as the first green-skinned portrayal of an evil witch. We are in full crone mode.

Decades of representations of good and evil as linked to beauty/ugliness, especially in Disney films, have spurred ongoing discussions about the racist, fatphobic, ableist, and queerphobic depictions of villains. The witch has been caught in the crosshairs of this othering.

Lately, however, the crone has been having a moment. Just this Halloween, I saw many Strega Nona costumes on my social media feeds (and I loved them all). Moving beyond the discourse surrounding beauty, the crone archetype is associated with wisdom, experience, and independence. She is often depicted as self-sufficient and connected to nature. In 2024, Strega Nona Fall took over social media in the wake of Brat Summer. Memes highlighted themes of community and green (magic centred on nature) and kitchen (magic centred on food and herbs) witchcraft. She became an anti-capitalist symbol:

Climate anxiety, the constantly crashing economic system, and the return of fascism in full force (because was it ever really gone?) has changed us. Much like the girl power era has come into question for its capitalist appropriation of feminism, so too has the twenty-first century girl boss trope.

My answer to Jac’s question, then, is another question: who is behind the season of the crone? Is it just another marketing campaign, meant to create a virtual aesthetic that will live on our screens? Or are we truly looking to the figure of the crone to subvert the ways we have been taught the world “needs to be”?

In the “you can be/achieve/do anything you want” era of our girl -powered childhoods, my own abilities never made me feel like a “freak.” The main characters of my favourite shows had to hide their “freak” powers from mere mortals. I see these as metaphors for our very real “girl powers” that we were, instead, encouraged to flex in the nineties and aughts: being smart, speaking up, dreaming big about our futures. Like many of my friends, I read a lot; I did well in school; I was both loud and shy depending on the moment; I believed in my abilities to see my goals through; I wanted to be an author, an artist, a teacher; I knew I could do any and all those things. I don’t take that for granted, especially in our current political climate.

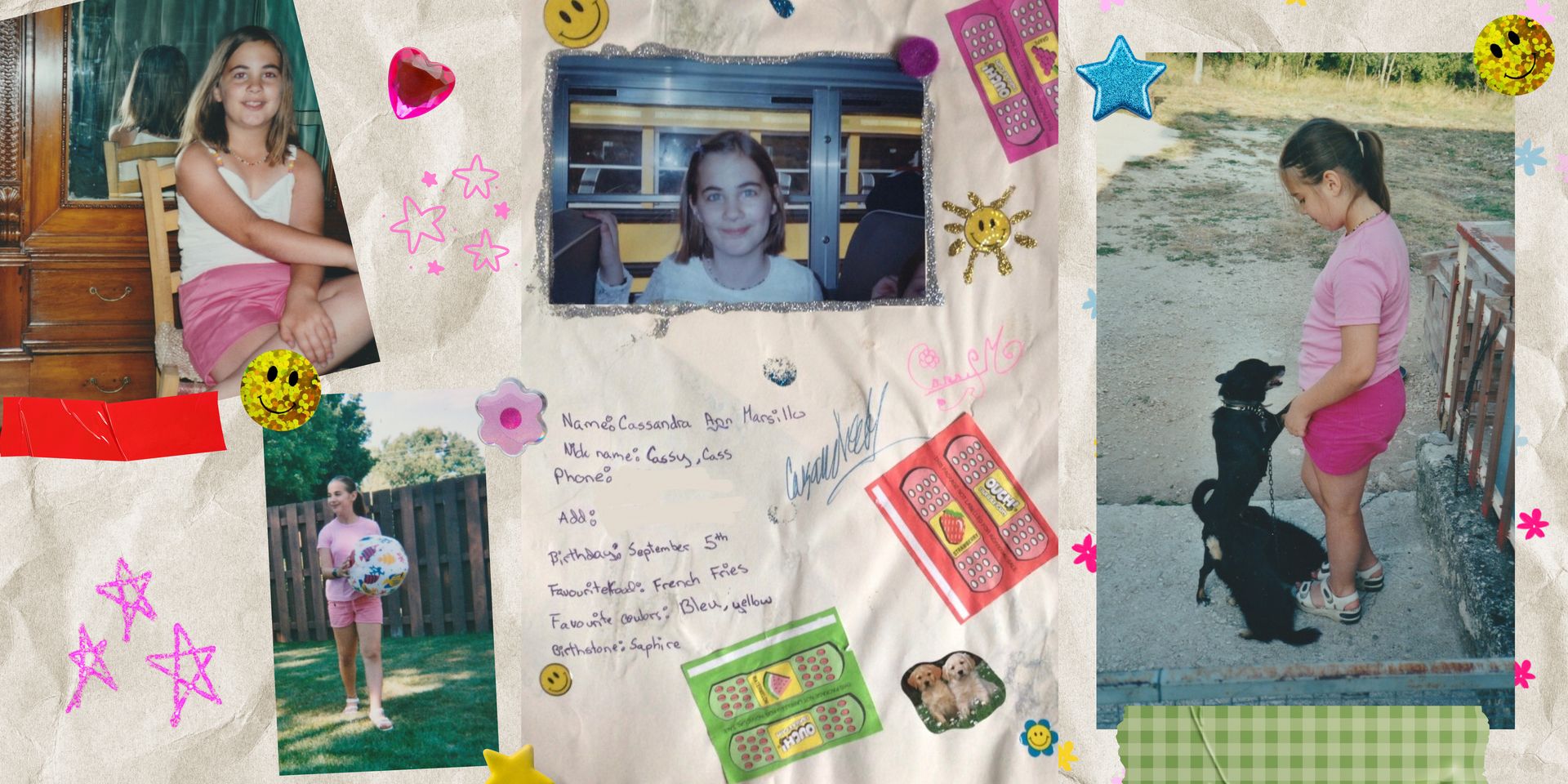

Though I’m in a much better place re: how I feel and think about my body, there are scars that will never go away. Comments I’ve (over)heard about my body lurk constantly, ready to float to the front of my mind, light as a feather, and rattle me from the inside out. Turns out my ability to recall these memories in great detail is a superpower of mine. While they can still sting, what hurts the most is looking at photos of little me, knowing that the spell of insecurity was already being cast.

I wish so much that I could release her from it.

Each newsletter is written by either Jac or Cass (hi!). In The Dish, this issue’s author asks the other (notyr)girl about what that month’s topic means to them.

Cass: Which witch (in pop culture/history/mythology) did you connect to the most? Why?

Jac’s take on the green witch.

Jac: I was never a particularly witchy girl, easy Halloween costume aside. I shared my mum’s disdain for astrology. My parents impressed upon me a love of education and scholarship from an early age. We were a family that believed in knowledge and science — I didn’t have time for adults playing make-believe.

As an elder (i.e. at the crone age of 34) my perspective has softened to an extent, in no small part because of my enduring interest in how knowledge is produced and ordered, as well as the history of science and health and its intersection with folkloric traditions. I have also fully embraced my excessively Leo self 🌞.

I admit over-the-top witchiness can still bug me, especially when overtly packaged and sold to us as part of some divine feminine tradition. What I cherish about the witches in my life is how they show up for me/one another. Witchiness as a practice of care and maintaining community outside strict capitalist relations? I’m here for that. Not for the $40 candles that we are told we need to live a specifically “female” lifestyle.

As a child, I was, however, fascinated by Greek myth. I have carried the stories of Medusa (not a witch, but a monstrous woman) and the sorceress Circe with me for decades. As an adult, my first tattoo was of Medusa, inspired by Hélène Cixous’ 1976 essay “The Laugh of the Medusa”. Cixous is interested in the paradox of writing as a woman who must employ language created by patriarchy. She argues for the creation of a specifically feminine mode of writing –which is not to say that only women can employ such a style.

Once you start looking for the effects of patriarchal language, you end up seeing it everywhere. When there are attempts to push back against regressive modes of storytelling, it often comes in the form of attempting to subvert narratives and reclaim stereotypes, but on the same terms as what has come before in a way that leads us right back where we started.

I eye the explosion of interest in Wicked and similar villain-redemptive origin stories with suspicion for this reason. Are we just trying to locate our shadow-selves in these stories? If yes, the kind of feminist retellings that feel like a first step towards this écriture feminine but fail to actually create. We are not simply doomed to repeat what has come before us. If we are to be witches, let’s magick ourselves to somewhere new and interesting.

Reply